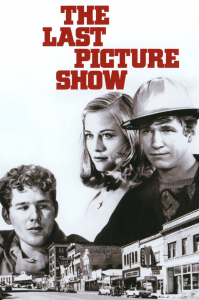

The Last Picture Show, an American coming of age film by director Peter Bogdanovich is an acclaimed American classic, notable for many star turns from individuals who would go on to find much later success, including Jeff Bridges, Randy Quaid and Cybill Shepherd. The movie seems a precursor to the advent of the teen coming of age genre that director John Hughes seems to have dominated throughout the 1980’s with modern day classics as The Breakfast Club and Sixteen Candles, and is truly ahead of its time when compared to the raunchy millennium take on the teen coming of age film, American Pie, which seems to have taken many of it’s plot cues from Bogdanovich’s early entry into the genre, including a teens loss of virginity, sex with a prostitute and sex with an older woman. Adapted from a semi-autobiographical novel written by acclaimed author Larry McMurtry, known for his other works including Terms of Endearment and Brokeback Mountain, The Last Picture Show can be seen as a typical coming of age film, which focuses on the psychological and moral growth or transition of a protagonist, in this case the character of Sonny, as they navigate the throes of life into adulthood. Though the importance of the film with it’s cultural and historical significance can’t be argued, that it is merely a film preoccupied with teenage sex should not be entirely overlooked, as the trajectory of the film seems to lead more towards the sexual experiences of the characters than of any true character growth of significance. As such, The Last Picture Show is truly not just a coming of age story, but also an American teen sex film that treats sex as the true basis of life as well as a catalyst to forge through whatever obstacles life may present.

While the film at first glance depicts one’s teenage years as a wasteland of angst and preoccupation, the film does a magnificent job of framing not only the pitfalls that sex has on one’s life as they are introduced to it, but the destructive nature that not partaking in it can have. The teen sex genre is one that reemerged near the turn of the century, though can be seen to have reached its peak in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s with films such as National Lampoon’s Animal House, Porky’s and Revenge of the Nerds, prior to The Last Picture Show. The basic plot of the 1999 film American Pie was a group of high schoolers making a pact to lose their virginity before they graduated. Much the same could be said for the overall plot and motivations of the lead teen characters in The Last Picture Show, as each seem to establish their own role and interest in sex throughout the film.

Bogdanovich makes it known early on that the film will deal with the wasteland that sex can be. The establishing pan shot of the film depicts a seemingly deserted Texas town of Anarene, starting at the movie theater down to the Texas Moon Café before focusing on the main thoroughfare which sees a pickup truck come speeding into the frame. As the Hank Williams lyrics “How come you treat me like a worn-out shoe, My hair’s still curly and my eye’s still blue, why won’t you love me like you used to do?” play, we are introduced to our protagonist, Sonny, the driver of that pick up truck that struggles through gear changes down the barren street. As Sonny continues, we are met with a revelation that contrary to the initial image shown, the town is in fact far from completely deserted. A long shot introduces us to Sonny’s friend Billy, who sweeps the city streets, as other characters such as Sam are introduced, showing us that the town the we thought to be a wasteland is actually filled with townspeople, who at the moment are disappointed with the high school football team’s inability to tackle or win a football game, a clear allusion to the lack of sex being had. No touchdowns are being had, a sports analogy that seems fitting to the lack of sex being had as well. If the team were involved in sexual escapades, would their fortunes on the field change? This disappointment seems to weigh on our protagonist, Sonny, who we come to learn leads a lackluster dating life with a lackluster girlfriend, Charlene, for whom sex does not seem to be as big of a deal for.

Sex is a definite focal point of the film, as expressed by noted film critic Roger Ebert, whose review of the film states how the town is “infected by a general malaise and engage in sexual infidelities partly to remind themselves they are alive. There isn’t much else to do in Anarene, no dreams worth dreaming, no new faces, not even a football team that can tackle worth a damn.” Sex is life, as detailed by the film. We are told that we are not to be interested in characters such as Charlene because of her lack of sexual nature, or willingness to pursue it all the way. Though she seems comfortable with making out topless with Sonny in his pickup truck, when Sonny moves to take things further, she is quick to put a stop to it, accusing him of trying to get her pregnant. The reaction establishes the character as not belonging in the world that the film depicts, and through her absence for the remainder of the film, reinforces the notion that a lack of interest in sex is akin to death, or simply not existing. As Charlene’s most memorable scene eventually leads with her and Sonny breaking up after proclaiming she would be saving herself for marriage, something that could be admirable to some, but within the world that Bogdanovich establishes, is not to be rewarded.

Charlene is a plain and homely character as portrayed in the film, a direct contrast to the character of Jacy, who we are first introduced to at the movie theater making out with her boyfriend, and Sonny’s best friend, Duane. Sonny clearly has eyes for Jacy, who is depicted as more attractive, and therefore more sexually desirable than Charlene. The next time we see Jacy is in the classroom, where the midshots of her that the scene cuts to repeatedly are of her admiring herself in the mirror of her compact. Jacy is presented to the audience by Bogdanovich as something to be attained, a theme that continues for the character throughout the film.

Sex is so important that even the animals of the film are doing it, as depicted in the background shot scene in the classroom where a bored Sonny finds himself staring out the window and a pair of canines are seen mounted in the distance while Joe Bob discusses the virtues of living a good Christian life. Joe Bob another character for whom sex seems important, but in a twisted way, as Joe Bob is later accused of pedophilia with a young child later in the film. That the film chooses such a path for the character who is the preacher’s son and speaks of Christianity and virtue clearly shows that those virtues are not what the film is looking to preach.

Sex heals all ailments, a lesson learned throughout the film by a number of characters. As we are first introduced to the character of Ruth Popper, played by Cloris Leachman, who is a depressed housewife of the school coach. As an affair begins between Sonny and Ruth, after Sonny is tasked with driving Ruth to a doctor’s appointment, Ruth begins to come alive, despite the awkwardness that is their first sexual encounter. The camera work shown during the scene in which Sonny loses his virginity to Ruth does much to establish the awkwardness of the moment, featuring a long shot of the two characters as they undress before each make their way to the protection and cover of the bed to engage in an act that forces Ruth to cry before it’s over. The close-up reaction shot of her as Sonny tries to pull away and she pulls him back to her demonstrates how determined Ruth is to cling to life. Sonny has officially become a man. As Ruth continues to develop feelings for Sonny, she begins to come back alive and out of her depression and ailment. When Sonny abandons her for Jacy, her ailment returns, as the character admits to being unable to get out of her bathrobe and carry on normal life activities, a true indication of the importance that sex and its healing nature has had on her life. As with Ruth, Sonny himself faces a sexual healing of sorts, as following a fight with Duane which results in his being blinded in one eye, Jacy’s suggestion of marriage, and thus the idea of being able to have sex with him, allows Sonny to quickly move past what should be a debilitating disability. It was the thought of Sonny and Jacy having sex that led to the rift and fight between Sonny and Duane, and the thought of it as well that led to Sonny accepting his current condition.

Throughout the film, sex is used as a weapon as well. Whereas the act is forced on non-understanding characters such as Billy, a simple boy and friend of Sonny’s, who’s mental handicaps prevent sex from being a focus of his mind. When his “friends”, including Sonny against his better judgment, present him to the town prostitute, the less than glamourous woman assaults Billy’s face when he prematurely ejaculates. As with Billy’s experience with the prostitute, Jacy is depicted as someone willing to use sex to her advantage and as a weapon when needed as well. “Everything gets old if you do it often enough,” she is told early in the film by her mother, who pushes for Jacy to leave behind her relationship with Duane, possibly turning her into the cold and calculating character that she continues to be throughout much of the film. Where as their relationship is initially shown as loving and innocent, such as in the scene where Jacy feeds Duane french fries as he lays his head in her lap at the drive in, it soon devolves to the point that when the two attempt to have sex simply so Jacy can not be a virgin for the rich boy she hopes to leave Duane for, Duane is unable to perform, repeatedly stating “I don’t know what happened.” Jacy’s descent towards the darker side of things is fully on display in the scene in which she attends the nude swimming party. The brazen young woman who seems fit to stand up Duane and attend the party on the arm of a class rival seems to disappear momentarily at the beginning of the party, as Jacy is met with a nude swimmer emerging from the pool. The close-up reaction shot of her shows her divert her eyes at the sight of the nude man before her, a moment of naiveté that seems to vanish once the character agrees to undress in front of the crowd atop the diving board. As Jacy peels her clothes off item by item, her descent into the pool is truly her descent into woman and the end of innocence shown by the film to be what life is like when sex is not being had. That the watch Duane had given her as a gift stops working upon getting wet is a symbol of the end of not just the relationship, but of Jacy’s innocence, and the girl becoming a woman.

What the film truly seems to show is that the fate of a life without sex is death, as illustrated by the fates and sudden passing within the film of both Sam and Billy, the two characters for whom sex seems most unimportant. Bogdanovich’s film firmly establishes that sex is an integral part of the coming of age journey that boys experience on their course to adulthood and becoming men, as well as the women with whom their paths will inevitably cross. Sex, as demonstrated through the film, is an integral part of life, arguably the part that sustains you and keeps you alive. It is in addition an all-American characteristic, one as American as a slice of warm apple pie.

WORKS CITED

Bogdanovich, Peter, director. The Last Picture Show, Columbia Pictures, 1971

Ebert, Roger. “The Last Picture Show Review”, rogerebert.com, https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/the-last-picture-show-1971